by Tricia Dewey

Calvary Episcopal Church is preparing for its 104th year of the Lenten Preaching Series, held during the six weeks of Lent beginning with Ash Wednesday, February 18. Well-known and up-and-coming preachers from both near and far take to the pulpit to talk about everything from Biblical texts to current events, poetry, and life in general. Think spiritual TED Talks. Hundreds of people attend the services on speaker dates and stay afterward for the famous fish pudding at the Waffle Shop.

Before Lent 2025, entering the church complex through Calvary’s back door off the parking lot facing BB King Boulevard was difficult to navigate. There were dead ends and dark hallways. A renovation completed just before Lent 2025 opened the space and improved connections between the buildings that make up the Calvary campus.

For the first time in almost 30 years, Calvary’s three buildings underwent a major renovation costing $6 million. The project began in 2023, paused midway, and was completed in early 2025, just in time for the Lenten season. Since 1843, Calvary Episcopal Church has occupied the southeast corner of North Second Street and Adams Avenue in downtown Memphis. It is the oldest public building in continuous use in Memphis. The oldest part of the church dates to 1843, the bell tower to 1848, the chancel to 1881, the adjacent parish hall to 1906, and the education building, the southernmost structure, to 1992. Over time, additions created a maze-like interior.

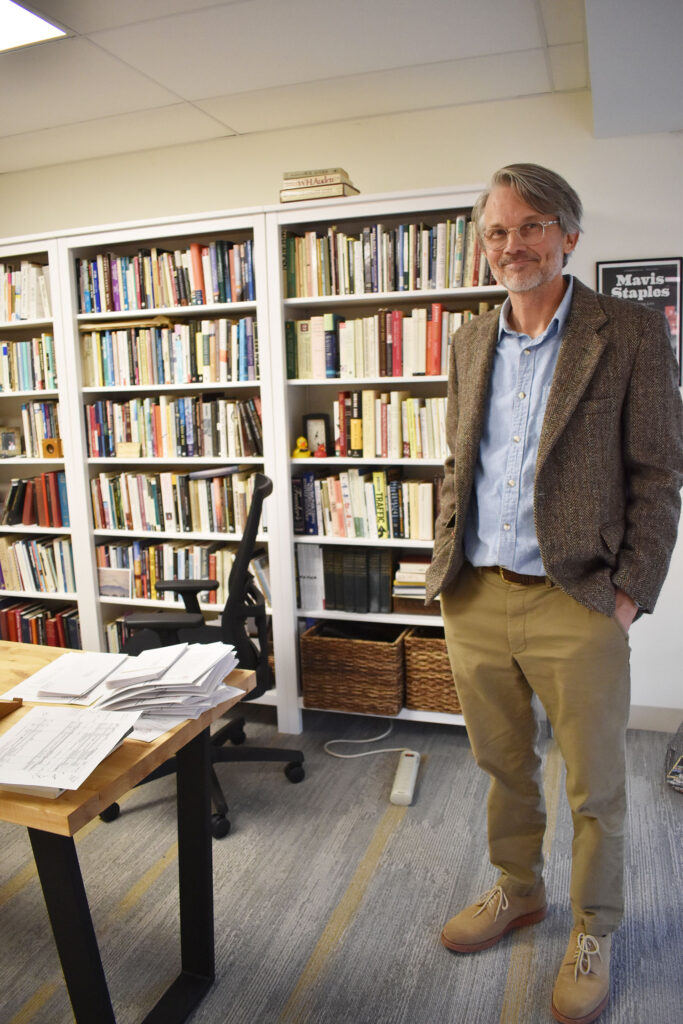

The Reverend Scott Walker, pastor at Calvary for the past eight years, knew at some point a construction project would be necessary. Renovation discussions in 2008 and 2014 did not move forward, but those false starts ultimately created new opportunities.

Walker described the deeper reasoning behind the project: “Calvary, in the way it interacts with the city, is a very open-armed kind of place in many ways. There’s a big outreach program to folks who are hungry and need clothes. Maybe 250 people come on a Sunday morning, and dozens and dozens of volunteers are helping. Medical students come to do foot care and HIV testing and all kinds of things.”

This openness also appeared in a healing service Calvary held in 1989, at a time when many people who died of AIDS were denied burial in churches. A banner fabric sculpture was hung from the church ceiling and has been displayed every year since 1989 through World AIDS Day.

Walker continued, “There’s been a posture of openness here, but the buildings were very closed off. You would be lost on the inside even if you got in here. If you came to the front door of the church and brought your child for the first time, someone would take you by the hand and lead you back down the hall, and you would leave your child in a place you couldn’t get back to on your own.”

Even during the Lenten Preaching Series and Waffle Shop, Walker said staff could be unaware that hundreds of people were in the building because they were insulated in fourth-floor offices or elsewhere. Choir members, children’s classrooms, and staff functioned in isolated zones. Instead of reinforcing a shared experience, the architecture separated ministries.

“So the driving force,” Walker explained, “was how to open the building and connect the areas inside.” For the congregation, it mattered how people encountered Calvary externally and internally. “If it feels like a fortress from the outside, and even once inside it’s hard to navigate,” Walker said, “that doesn’t feel very welcoming.”

Conversations about reimagining the space began in fall 2019, just before the pandemic. The church asked big questions: what could the buildings become if they were deeply renovated without limitations? Herron Horton Architects of Little Rock developed early concepts, focusing on the atrium in the central building as a point of orientation both vertically and horizontally.

The church itself was renovated first. “We still wanted it to feel like Calvary,” Walker said. Changes included streamlining the communion rail and creating a wheelchair-accessible path to the altar. The second phase, involving the parish hall and education building, was more complex and included relocating offices, adding a chapel, and raising the Montgomery Foyer. By delaying construction until after Easter 2024, contractors finished before Lent 2025.

During construction, services moved to other spaces, which Walker described as unexpectedly joyful. “It felt a bit like summer camp,” he said. Input from architects, the building committee led by David Lusk, and the congregation helped refine plans while staying true to shared priorities.

Today, the renovated atrium draws people in with light and openness. Visitors can now enter the Waffle Shop from this central point, and a new staircase leads directly to the back of the church. A second-floor loop, finished with matching hardwood, visually ties spaces together.

Walker believes the renovation ultimately achieved its goals more efficiently than the original plans. “We had to keep refining without losing sight of what mattered,” he said.

That intention is embodied in a large table in the staff room. “There’s a common table that symbolizes everything we were after,” Walker said. “We want to meet each other, see each other. These are spaces humans want to occupy.”

The architects applied for a National Fund for Sacred Places award for connectivity. Walker emphasized that connection is not secondary. “Meeting the stranger goes deep in the Judeo-Christian tradition,” he said. “A lightless hallway feels very different from windows, light, and people inviting you to sit at a table.”

Walker noted that staff initially worried about privacy, but the openness has strengthened collaboration and relationships.

Architecturally, Walker believes people are drawn to shared centers. “They stop by to drop off clothes. They wave through windows. These small interactions add up to real relationships,” he said.

On Wednesday nights, Calvary often hosts 80 people for supper, along with children’s choirs, adult choirs, and classes. The Commons now allows energy to flow between spaces. “Single people have access to families, families to elders,” Walker said. “If you divide by demographics, it’s a real loss. The architecture helps us resist that.”

Walker feels the renovation has renewed Calvary’s mission. “Welcoming the stranger is a moral practice,” he said. “Very few people are talked into new positions. They’re befriended into them. Architecture can help make that possible.”

As you walk into Calvary’s gleaming hallways for the Lenten Preaching Series, accompanied by the sound of the newly restored 1935 Aeolian-Skinner organ, you may find yourself a stranger stepping into history, waiting to be welcomed, or simply anticipating beautiful words and a Lenten waffle.