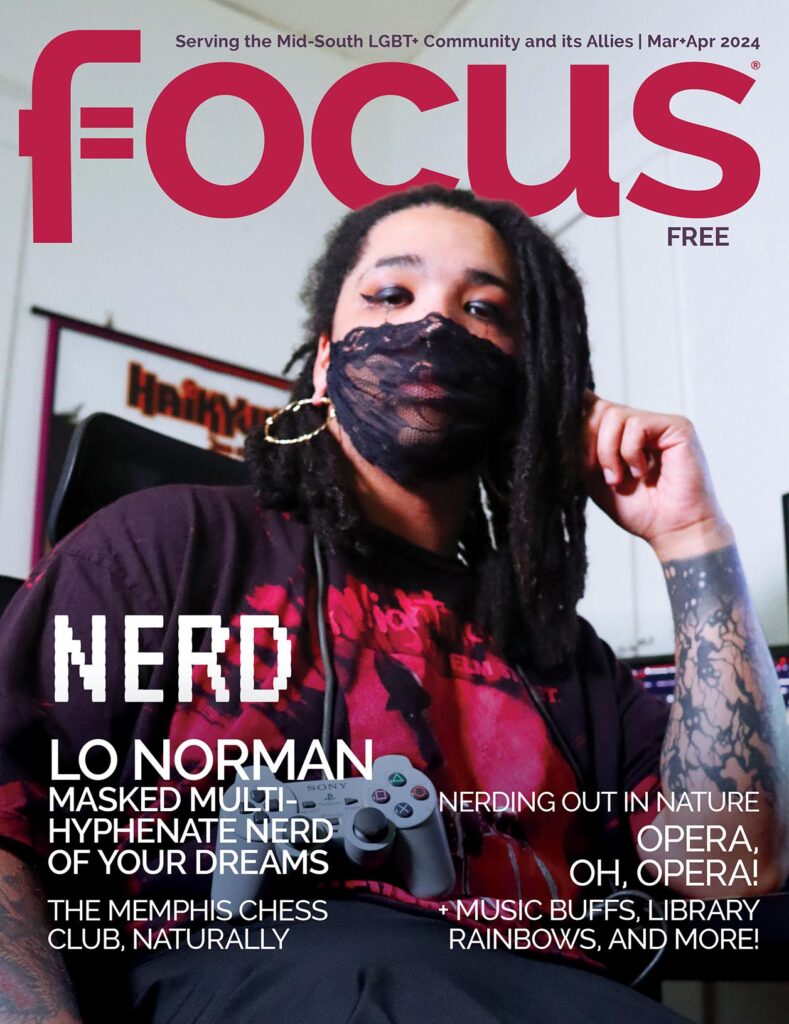

story by Chris Reeder Young | photos by Demarcus Bowser + Memphis Tilth

Where does nutritional health begin? Does it begin with a meal prepared by a restaurant, by you, by friends, or by family? Does it begin when we post images of healthy, sexy food on social media that spark a barrage of recipes requests? Does nutritional health start when we receive our Community Supported Agriculture (CSAs), pull our own carrots, grocery shop, or plant seeds? Is the fellowship of breaking bread considered a type of nutritional health as well?

When we think about farm to fork journeys, do we think about the role consumers have in supporting food producers who generate community nutrition and global human rights decrees? Yes, we know to eat our Wheaties, but what about being intentional, conscientious food consumers who encourage communal health, policy and engagement? Are we asking our local restaurants to support farmers of color when they cultivate their menus, and how are we making sure that Black Farmers Lives Matter?

Mia Madison, Executive Director of Memphis Tilth, explores some of these questions with us.

Memphis Tilth, modeled after Seattle Tilth, is a collective action organization that

improves socially and economically sound options for nutritional access, food justice

policy and capacity building for local gardens. Since its inception, Tilth has encouraged a local food economy wherein “people can grow food where little to no access existed before, and generate income by selling fruits and veggies in markets.”

Tilth mission focuses on growing local, farm direct food sharing, and facilitating nutrition-focused cooking classes. A perfect amalgamation of this mission is found in the St. Paul Garden: an educational garden space partnered with Advance Memphis and its commercial kitchen. This neighborhood anchor offers students and neighborhood stakeholders with urban agricultural training certificates and cooking classes (initially part of the Project Diabetes Grant). Additional gardens include the St. Jude Garden and community-led gardens in various parts of the city.

To tap further in Tilth’s mission, Madison shares, “to be socially equitable in farming,

and as advocates and policy changers, we must look across the landscape to find those who are disadvantaged growers or producers, and then connect them to partners, institutions and businesses to get farmers of color into markets fairly.”

She continues to highlight that “there is a lot of privilege around food; when we look

across farms in the Mid-South region, many of them are Black-owned farms. They are

producing fruits and veggies, but aren’t necessarily tapped into marketing opportunities or restaurants or organizations that promote and support them. They likely go through farmer’s markets, but there is so much more opportunity for them.” She further adds, “we need to move the needle on who we spend our dollars with, there are families who are from varying backgrounds who produce incredible products; we can help economically sustain communities of color with our support.”

Madison reminds us that so many people can learn about one another by broadening our cultural experience through diverse food sharing while also learning more about healthy eating from farm to table, “we have six different farms of color that we buy from for food shares. A question people can ask themselves when thinking about being inclusive in their food purchasing or menu creation power is ‘did I buy this food from a family who experiences discrimination because of their skin color or orientation’?”

In addition to fresh, healthy produce that accompany, grassroots-level cooking

courses like S.A.D. To S.O.L., consumers who create authentic and intentional relationships with Black-owned farmers break systemic patterns of disadvantage where White dominated agricultural spaces have been at the forefront of food production and marketing. Madison says “partnerships with farmers of color encourage Black growers to consider farming production as viable economic options for future generations. It is important for youth.”

https://www.memphistilth.org/urban-agriculture-academy

Another aspect of health that doesn’t appear as obvious is environmental health where communities are social determinants of health. Where people live impacts their health, in fact, zip codes often tell more about a person’s health than their genetics. In addition to promoting local community gardening, agricultural training, and nutritional health, Madison points out that Tilth helps to improve neighborhood conditions by creating food access opportunities, “we build a bridge with people and their built environment, it’s a blight reduction model which happens to be focused on food production so we can get more folks access to nutritional health and food while remediating overgrown green spaces.” Vacant lots and green spaces can turn into food sources and sites for cultural exchange and education, in fact, Tilth’s Giving Grove is exactly the process of building upon the assets of green space by introducing

fruits, nuts and berries “to increase access to healthy food and to strengthen community and improve the urban environment.”

Memphis has horticulturists, farmers, food justice fighters and communities who help us realize that the starting line of social justice and nutritional health starts way ahead of a photo-ready plate of food. Topics like food touring, food access, locally funded food hubs, and CSAs help us become intentional about where food comes from, how to support local food producers, and ways to prepare food that are both culturally, nutritionally significant, and sacred.

For people interested in supporting Memphis Tilth, you can donate so that funding

goes toward establishing local community gardens, paying forward Bring It Food Hub, and/or starting a Giving Grove. If you are the type of person who enjoys hands on volunteerism, you can work through garden spaces or Groves in communities or purchase trees directly from Tilth.

For people interested in supporting producers, please visit: New Way Aquaponics

Farm, Knowledge Quest/Green Leaf Learning Farm, Landmark Farmers Market, Lockard’s Produce, Anderson Farms, and Oka Nashoba Family Farm.