by Gabriella Lindsay

photos by Gabriella Lindsay

The Memphis Zine Festival recently celebrated its ten-year anniversary. Havenhaus, the downtown venue, was buzzing with creatives in conversation. At the heart of the festival was the a deep sense of community and a big love for zines. Walking through the festival, I noticed how many tables represented a different experience of being queer in Memphis and how my understanding of Memphis is more complete with their perspectives. But first, what’s a zine?

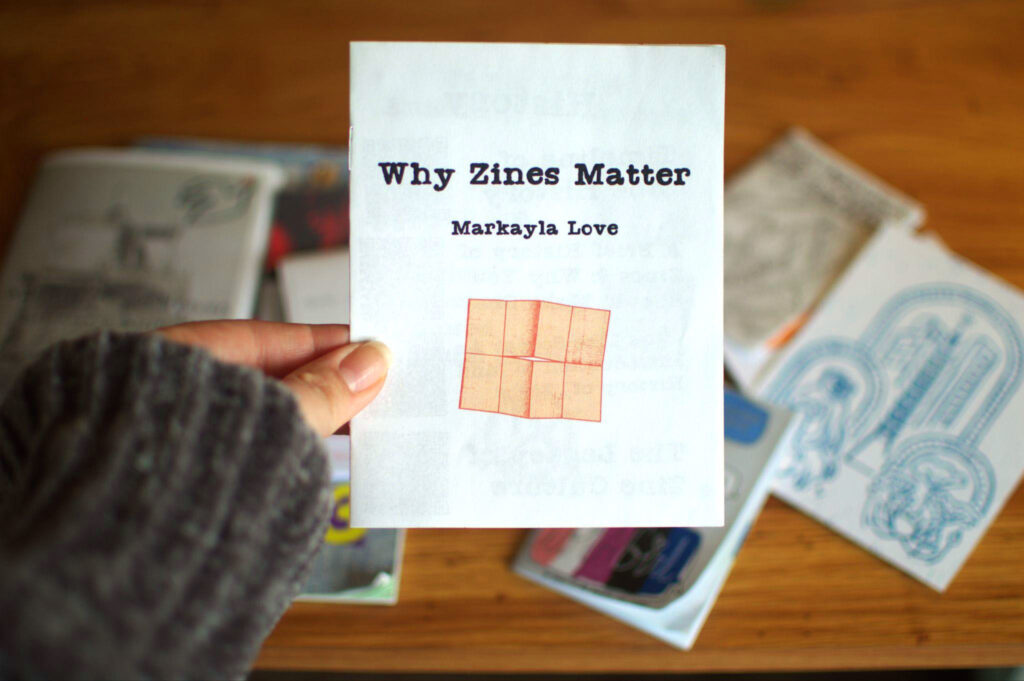

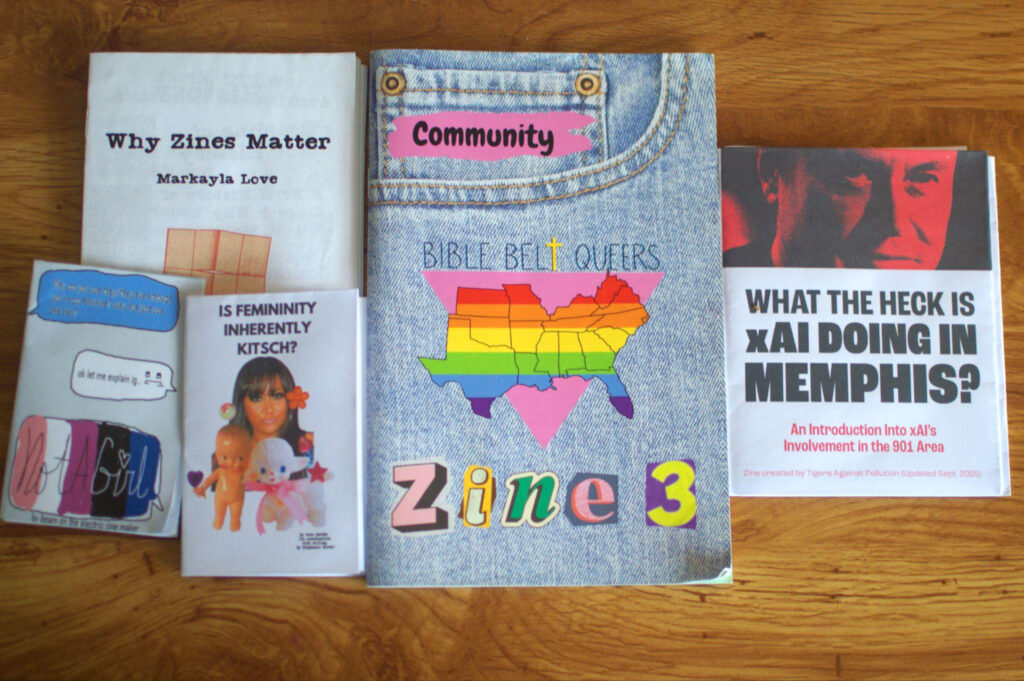

Zines are typically short publications (think magaZINE) and can be about anything. They can be personal or community-oriented, silly or serious, but always intimate. At the festival, the range of topics stretched from literary cannabilism to queer Southern love to a curated compilation of unhinged YouTube comments under Keanu Reeves vidoes. One vendor, Markayla Love, explains the economics behind the medium in their publication Why Zines Matter: “Zines are not created for profit; they are made to share ideas. This non-commercial approach ensures that information and art are accessible to everyone, with zines often sold for low prices, traded, or given away for free.” Because authors have to typically fund their own printing, zines are published in smaller batches, so circulation stays local. However, zine-makers counts this as a feature, not a flaw. Smaller reach means deeper connection. These publications are almost always exclusively offline—they are not meant to go viral. They are meant to start conversation and bring connection.

This philosophy informs many queer zines across the South, where visibility can be risky but community is still essential. This is why we began Cher, a collaborative Southern queer art zine that is exclusive to a small region in the South. Cher prints less than 300 copies per quarterly issue, and this limited distribution is intentional. Without commercial publishing, the distribution model is social. Contributors take copies to hand out or give to friends, and small stacks appear in queer-friendly coffee shops, libraries, and art collectives. The idea behind this publication is to unite and celebrate queer artists and writers in an area that votes against the LGBTQIA+ community. Cher can act as a beacon to a small locality, providing visibility and connection. At the Memphis Zine Fest, I found another region-specific queer zine called Bible Belt Queers.

Darci McFarland, founder and editor of Bible Belt Queers, widens the geographic reach but maintains the spirit of connection and mutual support. McFarland assembles queer voices from the sixteen Bible Belt states, curating the art and poetry of queer voices but also confronting legislative pressures shaping queer life in the region directly. For example, one of the contributors of the Bible Belt Queers, Mckinley Streett, uses zine-making to process the Arkansas anti-trans policy that bans people from choosing X as their gender on their driver’s license. Streett writes about the faulty justification the governor uses: gender must match to prevent fraud. Street highlights the deep irony in this justification since the ban actually forces intersex people to commit fraud by choosing a gender that does not match their physiology. This is the political power of zines: not virality or mass persuasion, but mutual processing and reinforcement. This kind of emotional infrastructure is vital for the LGBTQIA+ community.

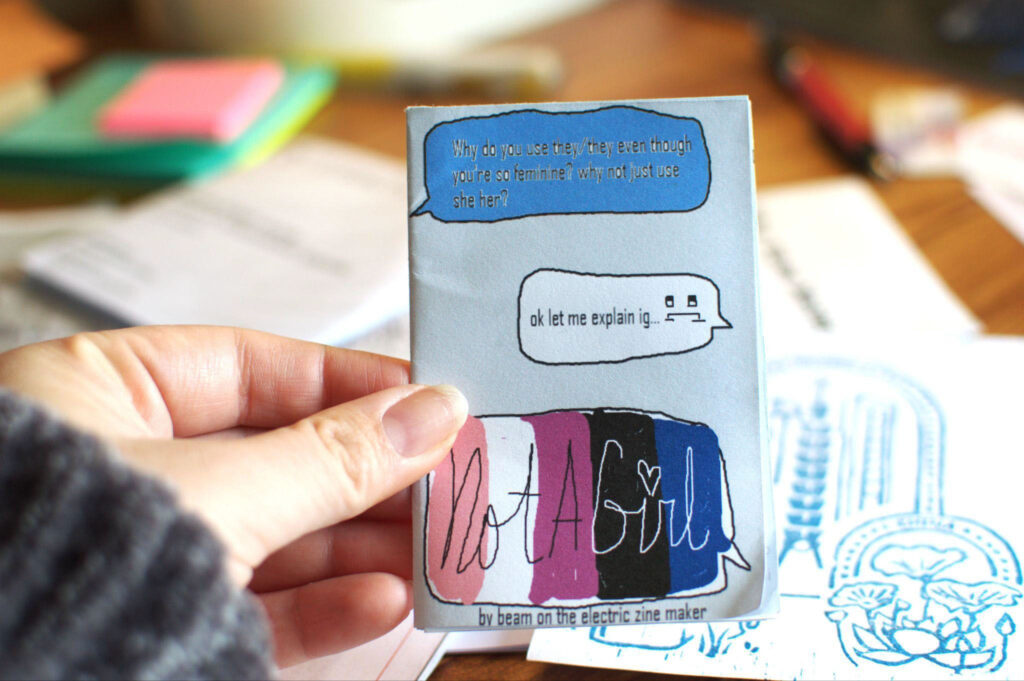

Down the same aisle, I found more zines tackling misconceptions about gender. Not a Girl, written by Beam, uses their gender experience to educate people about gender fluidity. They write, “I was sure of one thing as a kid / there was a way to be a Girl / and a way to be a Boy.” They say as they grew older, they learned there were people out in the world who were both. Pop star Prince blended masculinity and femininity to embody a walking rejection of gender norms. He even temporarily changed his name to a unpronounceable symbol fused by the male and female sign. Prince showed people that gender is theatre. Reading Beam’s zine let me walk through their gender experience in a way that helped me understand their identity far more intimately than a label ever could. And this is one of the great functions of zines: they are conversations, not labels.

As mentioned earlier, the point of zines is to share ideas, and some makers use zines not to tell personal stories but to think alongside others. Memphis zine-maker Wren Pardue does this with her zine Is Feminity Inherently Kitsch? Pardue’s zine engages with an essay by Stephanie Brown. Rather than summarize or quote Brown word for word, Pardue creates a dialogue between her own voice and Brown’s theories. This form allows for extension by personal perspective. This form is perfect for Pardue, who tells me that her artwork has a give and take relationship with feminism. This shone through as I read Pardue’s zine. It felt like listening to a conversation between two thinkers, puzzling over the oddness of femininity together. In a world where queer theory can be highly academic, zines like Pardue’s offer a more accessible way to understand queer studies and engage in the conversation.

While many of the zines at the festival dealt with challenges the queer community faces, I also found zines covering bipartisan Memphis issues. Tigers Against Pollution wrote an informative zine about the massive pollution harm xAI’s supercomputer is causing Memphis. They write, “The air we breathe and the water we drink do not discriminate along party lines.” Their zine provides resources and organizations for Memphians who want to mobilize and find activist opportunities.

But not all zines are heavy or theoretical. Some exist simply to introduce and highlight their creators. I found several zines used as business cards for local Memphians. One of these belonged to the founder of the Memphis Zine Festival, Erica Qualy. Qualy has been making zines for twenty years and leading zines workshops for the last decade. I asked her about the Memphis zine scene and she said it has grown a lot in the last decade. Qualy’s has had a large hand in this growth and one of the ways is by ensuring that the zine fest is free, queer friendly, and open to all.

As we chatted, I looked through her zines and noted how diverse a zine author’s collection can be. Qualy’s zines ranged from heavy topics like the Israeli-Palestine genocide, more personal work including selections from her art exhibition and poetry, and lighter works like listing her favorite dogs. Many creatives can find themselves cornered into one discipline, but zines allow makers to highlight their multi-dimensionality. While talking with Qualy, she asked me to pick a number. I picked and she read from page 7 of her zine, Facts, Advice, and Things to Think About: “Love is a garden. Water your plants.”For those who feel more and more disillusioned by the digital world and artificially created art, I encourage you to become involved with zines. The medium is for everyone: all you need is an idea, some paper, and the desire to connect with your community. The Brooks Museum of Art is holding a free zine-making event on December 13th. I hope to see you there!