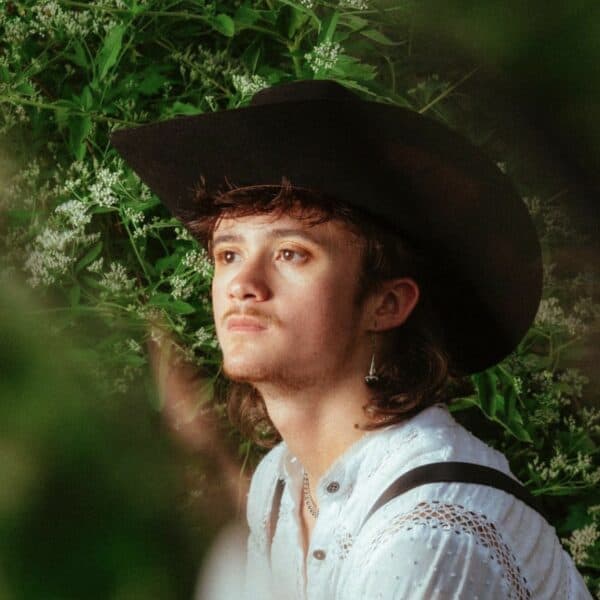

(Above photo: One of the only gravestones still legible and standing in the cemetery park, a descendant of the Eckles family. The burial sites of twenty-nine people enslaved by the family are still unaccounted for.)

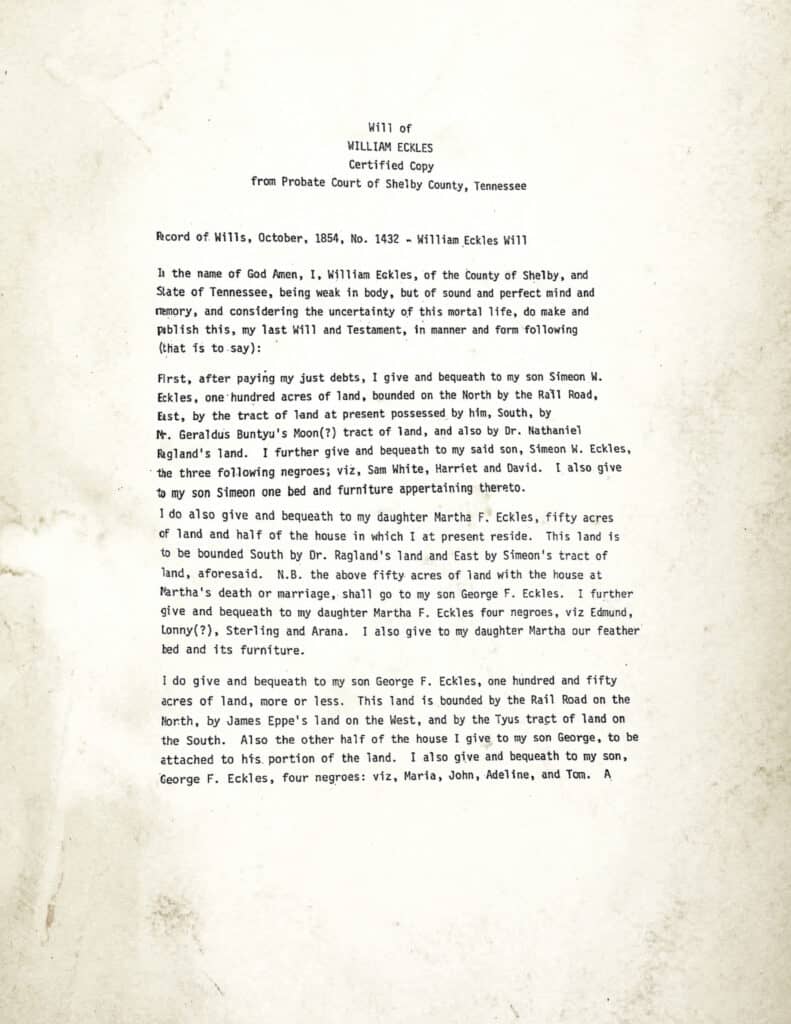

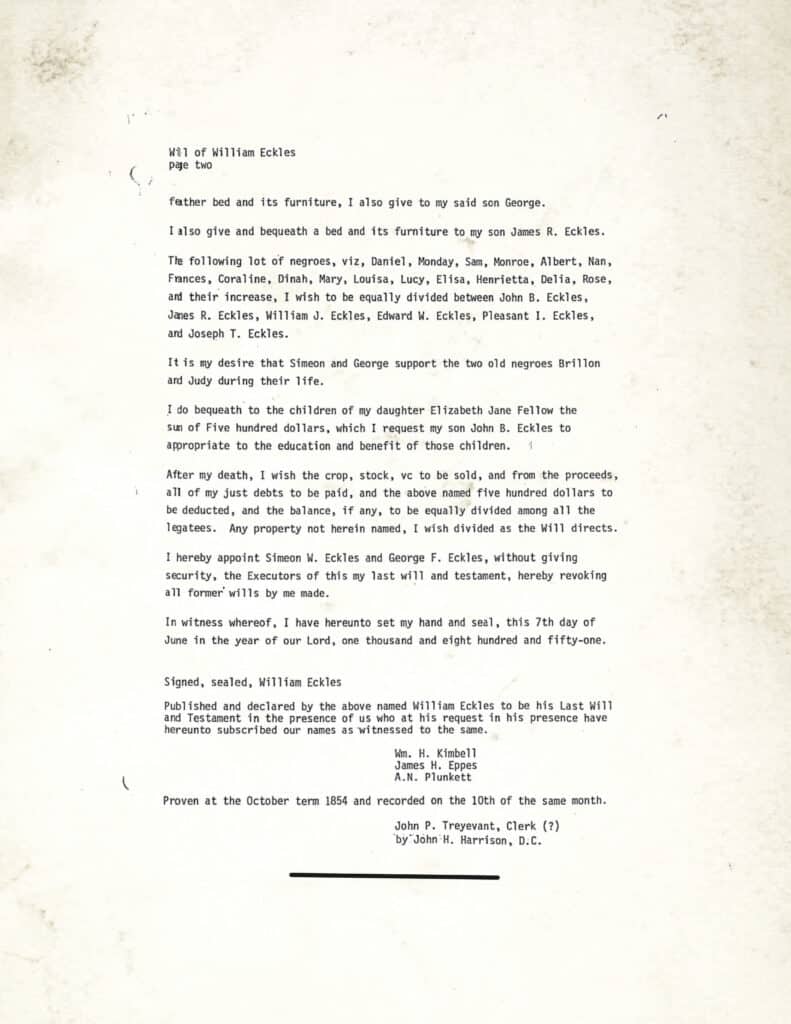

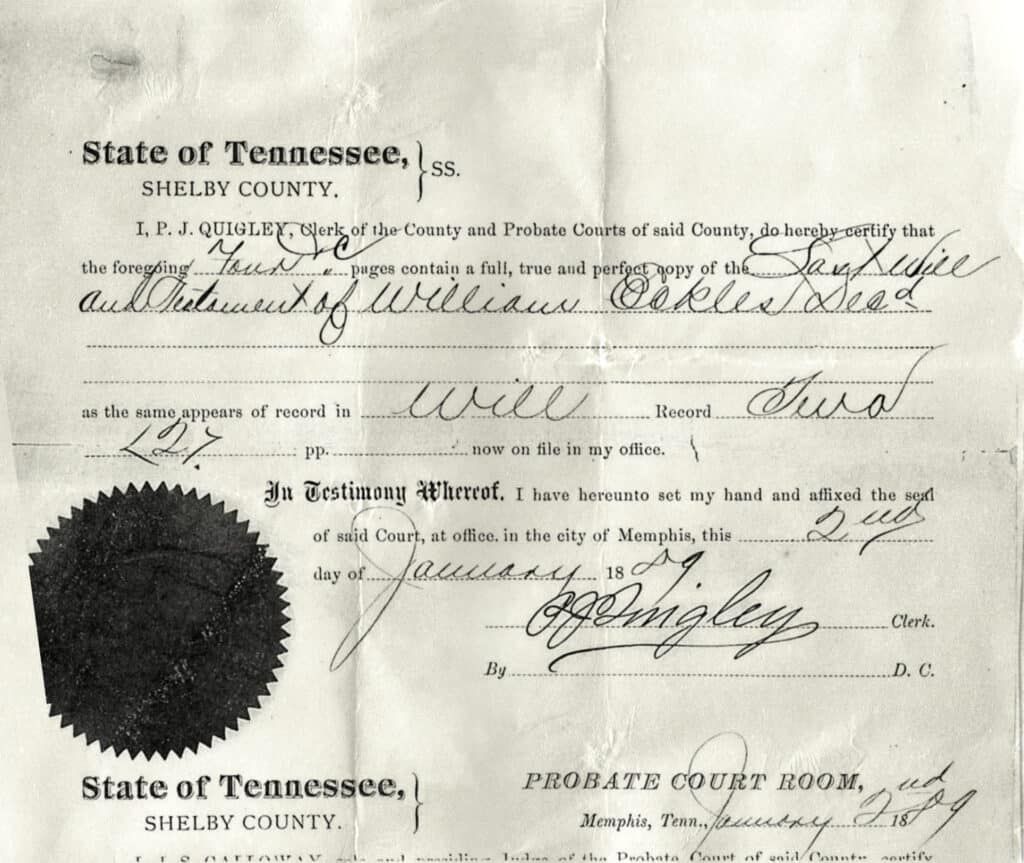

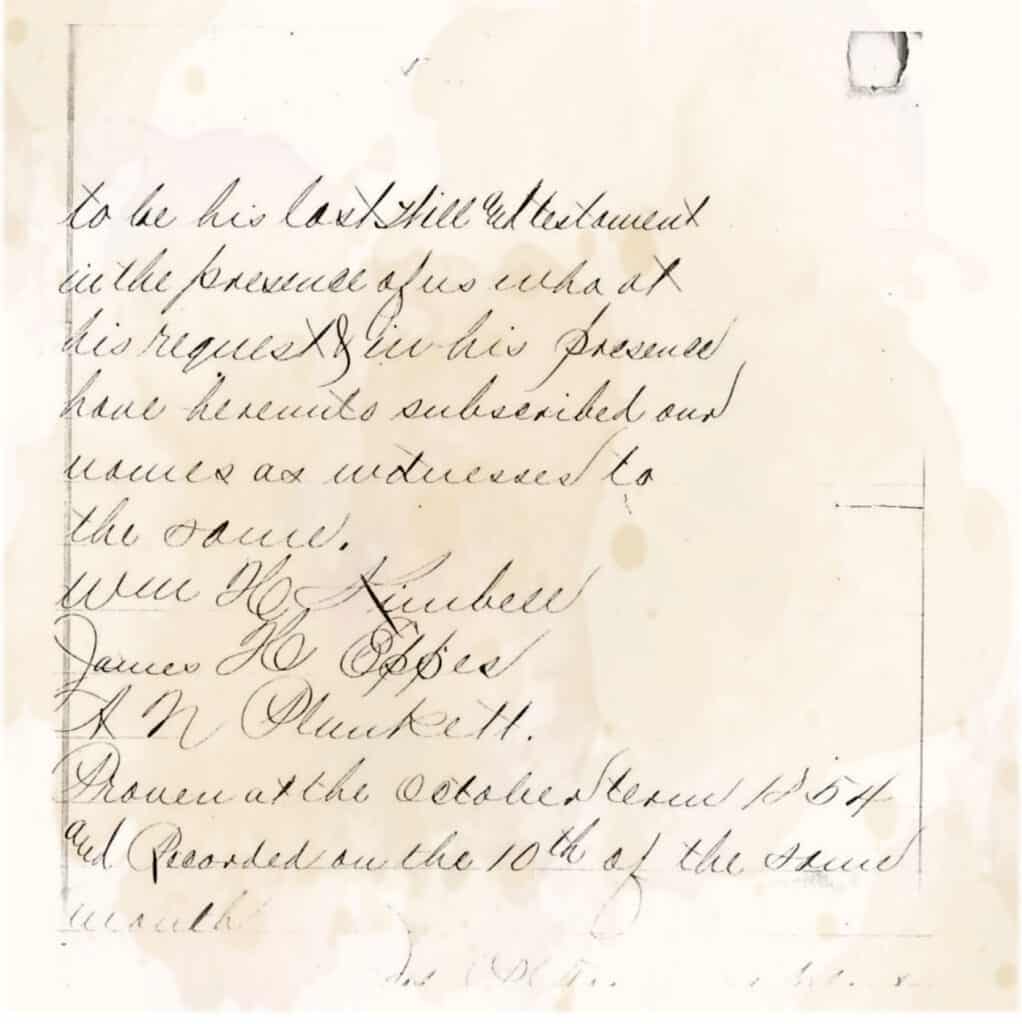

I am not a voice of authority. I am not a historian. Above all, I am not Black. I can not speak for the Black experience. It isn’t mine. I will not tell a story of the livelihood, conditions, and tragedies of enslaved people; it is not my story to tell. This account is merely based on my observations, speculations, and research on the Madison-Eckles cemetery, which was actively used from 1887 to 1926, located on the 3700 block of Normal Station. I lived next to the cemetery for three years. It was half a year before I knew I lived two lots down from the “secret cemetery.” While conducting research for this article, I came in contact with Nelda Fabish, who possesses a copy of William F. Eckles’, the father of Martha F. Eckles who

is buried in the cemetery, last will and testament from October, 1854. The will contains his distribution of assets, including the names of 29 enslaved people. The names of the people enslaved by the Eckles family are to be honored, remembered, and commemorated.

Sam White • Harriet • David • Edmund Lonny • Sterling • Arana • Maria • John Adeline • Tom • Daniel • Monday • Sam Monroe • Albert • Nan • Frances • Coraline Dinah • Mary • Louisa • Lucy • Elisa Henrietta • Delia • Rose

Fabish has previously released the will to First Congregational Church and a team at the University of Memphis doing research on the cemetery. However, this document has not been accessible to the public eye. I found this will through a comment from 2020 on a 2013 article about the development of the park and cemetery. The comment stated that Fabish “[has] information about the Eckles family that was found in [her] grandmother’s shed.”1 In her comment she stated that she worked at the Lowell Public Library in Indiana. I called her former place of employment and was transferred to several departments to get her my contact information. She had been waiting to receive a call.

I conducted thorough research on the Madison-Eckles cemetery and one question stuck in mind: why don’t any of these publications mention slavery? The only remark I could find was from High Ground News which stated:

“…archeology students [at the University of Memphis] research[ed] the history of the cemetery. In addition to ten marked gravesites, ground penetrating radar revealed the existence of additional burial sites (more investigation is needed to determine the precise number), which are located on the west side of the park, and may have belonged to servants or enslaved African-Americans.”2

The reports of who is buried in the cemetery varies according to the source. From the information I have found, the gravesites acknowledged in public media are as follows:

Memphis Heritage: 5 named3

Commercial Appeal: 19 bodies4

High Ground News: 5 identified, 5 unidentified additional unquantifiable graves5

Find-A-Grave: 6 known graves, 5 marked graves; Names: Martha F Eckles (1887); George F Eckles (1896); Francoise Xavier “Francis” Bibert (1910); Susan Rebecca “Sue” Phillips Bibert (1917); Harry Madison (1926); John O Farrell, certificate of death and obituary only (1938).6

The Normal Station Neighborhood Association, or NSNA, teamed up with the University of Memphis in 2013 to establish a park at the cemetery. After gaining ownership in 2014, the NSNA created brick walkways, planted native vegetation, and cleaned up the overgrown and littered lot. Historically, cemeteries served as a peaceful green space where individuals could congregate in familial fellowship. The goal of the Madison-Eckles Park Cemetery project is, as stated in High Ground News by Community Safety Liaison, Tk Buchanan, at the University of Memphis, “we’re hoping more and more people use it as a green space… It belongs to everybody, and we want everybody to use it and enjoy it.”7 I will foremost state that I am in support of the park. As a proud former residency in Normal Station, I am excited to see the cemetery cleaned up and the gravesites acknowledged. However, information has been intentionally kept from the public. Knowing that specific names of enslaved individuals had been distributed but not memorialized shifted my frustrated curiosity to complete dismay, specifically towards a collaborator of the project and my alma mater, the University of Memphis. As Nell told me, “I wanted to make sure that they weren’t forgotten and the story wasn’t forgotten.” She was hoping that by sharing the will, there would be a dedication to the enslaved people kept by William F. Eckles. The Madison-Eckles Cemetery Park, although currently under development, does not currently acknowledge slavery and the potential for burial sites of enslaved people.

“This comment is directed to the Normal Station Neighborhood Association: if you are going to commemorate history, commemorate all of it.”

I hope the article can serve to highlight the many ways in which our local, national, and international history has been curated to leave out voices of the oppressed. I could understand a perspective that desires to appease the public by disregarding information that may protect those in power; however, I stand with extreme disappointment. If there is to be a park commemorating the history of the Madison-Eckles family, the truth must be acknowledged and it would be a disservice to our city if not. This comment is directed to the Normal Station Neighborhood Association: if you are going to commemorate history, commemorate all of it. State how when the land was purchased in 1835 by William F. Eckles it was occupied by the Chickasaw Nation along the Black Bayou, a small river in Normal Station that was channelized in the 1940s. State how the Madison family sold their land in pieces from 1911-1914 and for 25 years restricted business or black individuals to own the space “to keep property values high.” State how The West Tennessee State Normal School, which opened in 1912, required its students to be white, 16 years of age, an elementary school graduate, physically fit, of “good moral character… and some responsible person.”8 There is no room in this city for historically curated racism. It is time to alter our narrative. I ask of you, the Normal Station Neighborhood Association, to respect and observe all the people that occupied our neighborhood, not just those in power. It is time for the transparent truth to be told.

REFERENCES

- Jerald Harris, “Normal Station Residents Seeking Improvements to Abandoned Cemetery,” Micromemphis, October 10, 2013, http://udistrict.micromemphis.com/home/normal-station-residents-seeking-improvements-to-abandoned-cemetery

- Scarlet Ponder, “University District Partnership Transforms Neglected Cemetery into Tranquil Park,” High Ground News, January 3, 2019, https://www.highgroundnews.com/features/MadisonEcklesCemetery.aspx.

- Memphis Heritage, “Cultural Resource Survey of Normal Station,” Memphis Heritage Inc., 2001, https://www.memphisheritage.org/normal-station.

- Jael Hardaway, “Decrepit Normal Station Cemetery Now in the Hands of Residents,” The Daily Helmsman, September 20, 2021, https://www.dailyhelmsman.com/article/2021/09/decrepit-normal- station-cemetery-now-in-the-hands-of-residents.

- Ponder, “University District Partnership Transforms.”

- Jim Hooper and Vanessa Hays, “Eckles-Madison Family Cemetery in Memphis, Tennessee – Find a Grave Cemetery,” Find a Grave, 2023, https://www.findagrave.com/cemetery/2249675/eckles-madison-family-cemetery.

- Ponder, “University District Partnership Transforms.”

- Memphis Heritage, “Cultural Resource Survey of Normal Station.”