by Vincent Astor

It was one of the saddest days in the history of Grace Episcopal Church. A very young parishioner, 17-year old Frederica Ward, was being laid to rest. She had sung in the choir and had a “decided turn for amateur theatricals.” Her coffin, with a glass viewing window, was almost completely hidden by white roses. One newspaper account described the wonderful concealment of wounds on her face. The church was filled and a large crowd filled the area outside the church and much of the available space up and down Vance Avenue. She was taken to Elmwood Cemetery and interred in a group lot belonging to the church. The interment was witnessed from a respectable distance by the large crowd.

The note in the parish register reads, “1892, 27th Wednesday A.M. Funeral—I read the Office for the Dead over the baptized body of Fredericka (sic): Daughter of Thomas Ward and Cornelia his wife who was born March 5th, 1874 & was brutally murdered in the City of Memphis, Tenn., by Alice Mitchell—January 25th, 1892. Geo. Patterson, Rector.”

Alice and Freda had met at Miss Higbee’s School for girls in Memphis. Freda, her friend Lillie Johnson, Alice, and Freda’s sister Josephine became fast friends.

Alice and Freda’s closeness was not unusual for the time, in fact sleepovers and obvious signs of affection were part of the practice of “chumming.” These relationships were thought to be “practice” for the later bond of matrimony when the relationship would change with the presence of a husband and children.

But Alice became obsessed with Freda – and jealous. Freda was known to be a flirt and seemed to see Alice as one of many people after her attention and affection. There were several small episodes that proved Alice’s seriousness about the relationship.

Even when Freda’s family moved to Golddust, a short boat ride up the river, in order to improve the family fortunes, the girls remained close through letter writing.

Ada Ward Volkmar, Freda’s older sister, had married and was living in Golddust. She discovered letters between Alice and Freda, and a ring. In the letters, the girls discussed their plan for Alice to dress in men’s clothes, marry Freda and flee to St. Louis together. Alice would live as Alvin J. Ward and find work to support them. Freda had accepted Alice’s proposal.

Ada was shocked and disgusted by the relationship and forbade any further communication between the two. Freda did as she was told, but was able to visit Memphis occasionally.

Alice frequently visited mutual friends hoping that Freda would be visiting too. In January of 1892 some secret communication convinced Alice that Freda still loved her. By this time, though, Alice had stolen her father’s razor and seemed to be edging towards a breaking point.

One day while sisters Freda and Jo had been in Memphis visiting friends, Alice, who knew Freda’s whereabouts, invited Lillie to take a ride downtown in the family’s horse-drawn wagon. Alice left Lillie with the wagon and found Jo and Freda who were walking down to the river to board a boat that would take them home to Golddust.

With her father’s razor in hand, Alice attacked first Freda, then Jo. The injured Freda tried to flee, but Alice caught up to her again, and this time, she slashed her throat and ran back to find Lillie who was still with the wagon.

When Alice returned, Lillie exclaimed about the blood that was on Alice, but Alice only wanted to leave, so Lillie took her home.

It didn’t take long for police to identify the killer, and Alice and Lillie were arrested later that night. Judge Julius J. DuBose heard the charges and indicted both girls. Lillie was later released on bail but Alice had to wait several months for her trial. Her father and attorneys entered the plea of “present insanity” meaning that she was insane before the murder and unfit to stand trial. Judge DuBose, himself a colorful historic character, presided over the trial.

Many of the letters between Alice and Freda were entered as evidence. When Alice’s attorney, General Luke E. Wright, finally questioned her, he asked “Why did you cut her?”

“Because I knew I could not have her and I didn’t want anyone else to have her,” she said.

“You intended to kill her?”

“Yes.” Alice replied.

“Now, Alice, why did you kill her?”

“I killed her,” Alice said, “because I loved her.”

Alice was found presently insane on July 30, 1892. All charges against Lillie Johnson were dropped. Alice was ordered to Western State Hospital for the Insane at Bolivar. She was granted permission to visit Freda’s grave on her way there. At the grave, Alice wept openly.

Just 6 years later, in 1898, Alice died. Her cause of death is somewhat disputed. Records say both tuberculosis and possibly suicide in the asylum water tank.

She was also buried in Elmwood Cemetery in her family’s plot. Her beautiful marker is close to the road and her story is part of the public tour.

Freda is buried with several others in the Grace Church plot now owned by Grace-St. Luke’s Episcopal Church. No markers were placed for any of the interments in this lot, but a tree dedicated to Freda grows in a spot nearby. A cenotaph was placed beneath the tree in December of 2017, 125 years after her death.

A full account of Freda’s murder may be found in “Old Shelby County” magazine, issue 40. The magazine is online on the County Register’s website register.shelby.tn.us/.

The book “Alice and Freda Forever” by Alexis Coe (2014) is available in bookstores and online.

In April of 2018, A Pretty Little Room, an opera scene telling the story of Alice and Freda, will premiere at the Midtown Opera Festival. Three additional scenes in this opera, commissioned for the festival, will also be Memphis-related. The title comes from a newspaper description of Alice’s room at the asylum.”

Freda’s Grave Gets a Marker

by Joan Alison | photos by Patrick Whitney

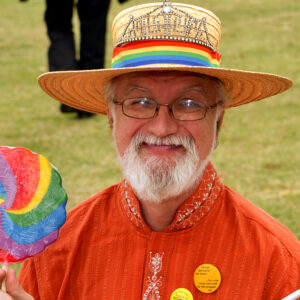

Freda Ward’s grave finally has a marker thanks to local LGBT+ advocates Audrey May and Vincent Astor who helped

Freda Ward’s grave finally has a marker thanks to local LGBT+ advocates Audrey May and Vincent Astor who helped

dedicate the new stone in December. The young murder victim died in 1892 after her former spurned girlfriend, Alice

Mitchell, slashed her throat.

It’s not clear why Freda Ward was buried without a grave marker in 1892 in her church’s cemetery plot at Elmwood. Thanks to local activists, there’s one now, just for her.

December 2, 2017 in Memphis was lovely. The weather was unseasonably warm and sunny, and could not have been more perfect for the St. Jude Marathon, and the Memphis Christmas parade that took place downtown on Beale Street.

About a mile from Beale Street, a small group gathered around a gravesite at Elmwood Cemetery. The interred, Freda Ward, had been buried there 125 years ago, the victim of murder. Her killer was Alice Mitchell, Freda’s former romantic love interest.

Alice, herself, died in 1892 in prison at Western State in Bolivar just a few months after she was sent there for the murder. At the time of her death, Alice’s body was returned to her family who buried her at Elmwood in the family plot and marked the grave with a beautiful headstone.

Rev. Gillian Klee, (in black vestments), the Chaplain at Constance Abbey, delivered the blessing of Ward’s marker.

Rev. Gillian Klee, (in black vestments), the Chaplain at Constance Abbey, delivered the blessing of Ward’s marker.

Here, she watches as members of OUTMemphis’ Pryzm group place flowers on Freda’s grave.

Freda had been laid to rest in 1892 in Grace Episcopal’s church plot, but with no marker. There is a tree to mark the area where she was buried, but there has been no engraved stone for Freda. Recently, local LGBT activist Audrey May decided to rectify the situation.

“(Vincent Astor) has been the one who kept reminding me, ‘Freda needs a marker, too.’ And she did, and now she does.” May said. “Vincent paid Elmwood for the land…and I paid for the marker by Crone Memorial.

“Vincent, as an Elmwood docent, did tours including (Alice and Freda), and convinced Elmwood to add them to the general tours. Elmwood, especially the director and assistant director, have been supportive and helpful all along.

“In the 125th year after Freda’s death, the tours will now be complete,” May said.

Audrey May, a former Board member at OUTMemphis, stands behind Vincent Astor (center, white shirt). The attendees also visited the grave of Ward’s former girlfriend turned murderer, Alice’s Mitchell. Mitchell’s grave has always been marked, and is in the Mitchell family’s Elmwood plot.

Audrey May, a former Board member at OUTMemphis, stands behind Vincent Astor (center, white shirt). The attendees also visited the grave of Ward’s former girlfriend turned murderer, Alice’s Mitchell. Mitchell’s grave has always been marked, and is in the Mitchell family’s Elmwood plot.