It’s eight in the morning, the beginning of February, and my bus is leaving the station. I’m nerve-wracked but excited about spending two weeks on the road. First:I head to Portland to see an author on his book tour. Afterwards, I will take another bus to my old college town, Missoula, in Montana. Then, finally, I will traverse another three days following the Mississippi back home. In my possession are: (1) a blank notebook that I intend to fill with poetry; (2) a book by the author I am going to see; and (3) a couple of granola bars for the road. My attention is firmly set on the world outside my window. I see a lone horse grazing by a power station. Let the journey begin.

Just outside Little Rock, after we pass by a thousand tarpaper homes and abandoned farms, there’s a sign for the AR POWERBALL. Its slogan simply states: IMAGINE! YOU WINNING! I write this down as a motif in my poetry book since I can’t pass up a good metaphor. And it certainly applies to a few moments.

As we coast into Texarkana, our first pit stop, the driver informs the passengers that we have thirty minutes. He adamantly admits that he will drive off without us. So, I make ample use of my time, by relieving myself and buying a few Gatorades. When I pop back onto the bus, the driver wastes no time shipping off.

But, not two miles away from the depot, the bus breaks down. Most of us, including me, wail because our transfer waits in Dallas. I certainly can’t afford to miss it. I cannot be stranded in Texarkana. One businessman angrily leaves the bus and says to just come back for him, he’s going to wait at the depot. Our driver tells him we won’t come back for him, but he just tells the driver he’s full of ‘bull shit’. But, the driver wasn’t lying since, not two minutes later, the bus leaves without the man. I watch him become a distant point in the winter void behind us. Imagine. You winning.

After that dead-of-night departure from Dallas, our ship of sailors swings into Amarillo around two in the morning. Here’s this American scene: ponytail drug deals, businessmen sniffing their fingers; migrant mothers, holding their crying children like the Pietà; and, one of many characters on my journey, a broken beatnik searching the routes for answers

His name is Rick. And he’s been everywhere. From his home in California to Montana to NYC to New Orleans to this stop right here to ask me if I could watch his bag for him. We have become fast friends, popping each other’s backs and watching those backs in turn. This is the communion of the road, I soon realize. You have to trust people.

Where his final destination was or would be, I do not know. He departs my life in Salt Lake City, refusing all of my gifts, all of my offerings. He knows the ways of the road better than I ever could. So I ordain him a saint of the streets in my heart.

I might be painting a desolate picture, but I don’t mean to. There’s beauty on the road as well. A great example comes from my poem Colorado Dawn.

“A picturesque pastoral of / muted grey and soft blue rekindles / when a daffodil paintbrush lifts up / the veil of night. A frontier fire blazes up again, / where cattle and horses lazily graze (…) / I open my canteen and swallow / cold clear water from a river running freely / about a mile past the horizon. (…) Outside, a few cattle moan like whales do at breach.”

There are many more moments like this during my travels, where the road takes on this ethereal quality. Moments where you can’t see anything but the world’s real beauty. It makes trips like these worth it, by car or by bus.

Another wonderful moment comes after my Portland stay. I hop onto my bus to Montana and meet a lady named Pixie. She’s an ex-Mormon lesbian with doll-red hair, and, I later found out, she had been confirmed in her former faith the same day I was born. Throughout the night we talk and smoke weed at every bus stop with watchful eyes. The drivers and depot authorities will find any excuse to kick you off the trail. Especially if what you’re doing is on the edge of legality.

One such instance happens during the Olympia station stop. Two elderly travelers try sneaking a garbage bag full of PBR into the underside of the bus. Of course, the bag rips open and beer spills out everywhere. Both culprits blame each other but the cops don’t care. They both get escorted off the property.

In Spokane, where Pixie lives, we say our goodbyes. She leaves me with the rest of her weed and a lovely kiss on the cheek. My next destination will be back to the halls of memory, back in Missoula.

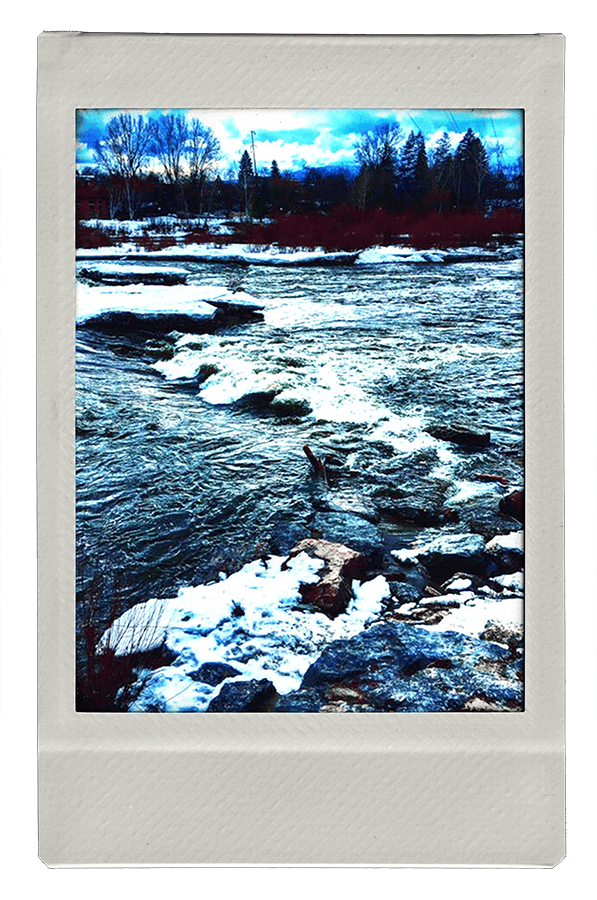

Missoula is shaped like a bowl, because it used to be a glacier.

The winding passes where the Clark-Fork rushes through, whipping cold wind like a cat-o’-nine-tails to the face. In fact, I describe Montana perfectly in my poem Passing into Montana, where I say:

“canyons, with their / creek cut bottoms; / pines hiking uphill; / snow; / train tracks; / river’s run; / snow; / icy roads;/ ice flows; / deer grazing; / eagles hunting; / snow; and / snow; and / snow.”

When the bus drops me off at the depot, I’m facing that wind, marching towards my friend’s place where I’ll be staying. You can save money when you travel by having people you know at each stop. That, or budget for a hotel.

Firstly, I go back to the college and visit all my old stops. It’s all stayed the same: bleary-eyed students working on assignments; teachers sipping their morning coffee. After a short nostalgia trip, I go back downtown, get a burrito from Taco Sano, and bother the baristas at Butterfly, just like old times. In that coffee shop, I write down in my poem Missoula, that:

“Nothing’s changed really. / The ghosts still haunt where they haunt / and I stick to the same old routes. I stay / on the paths I know and have known.”

There’s nothing bad about that. Sometimes, an oasis is all you need on a long journey. After a few days and an assorted adventure that I further detail in the poem I quoted, I got back on the bus to head back home.

My next destination: the Mississippi River, on my way home again. On the trip to the mouth of that great river, I nap. A man from Nigeria had given me his pillow to rest my head on. I want to thank him, but he departs while I sleep. The trip back home is just as eventful as the trip out West but without much beauty. It has the equivalence of a comedown or a hangover. The party’s over, so all I have left are storms and cornfields.

Still, I scribble down poems about this side of the country. In The Woods Grow Dark and Deep, after the Iowa cornfields,

“we find ourselves in a stalemate / the sky outside opening [up] for a storm. / The drone of wind and low- hanging / fruit of one-paycheck-away patrons / seems to me the perfect mix / for tornado warnings / and hurricane dreams.”

Well, just before we reach Little Rock, that exact storm descends.

Tornados, two of them, make us crest to the roadside and wait. It reminds me of Job getting yelled at by God, which I use in, Coming Home Again. I write how, if there is a God, then He made all of this,

“the sun and moon / the stars and sky / the earth and sea / the tragedies / the comedies / the singing homeless / the bastardizing rich / the hopeless and callous / the young and dumb / the old and worse!”

While we sit here, a man starts wandering up and down the bus, yelling about how he’s been stabbed. This man must be our modern Job himself. But no one cares. Because at the moment, I think all of us felt like Job.

All I know is I’m glad that home is a short three hours away.

There’s this surreality you can only experience when you take a long trip like this. Plus, a strange camaraderie exists on this long road. People like Pixie and Rick are maybe some of the kindest people I have ever met.

Would I do this again? Possibly a shorter trip. Maybe to the East Coast.

Do I regret the trip? Not at all. I’m glad I got to see America right.