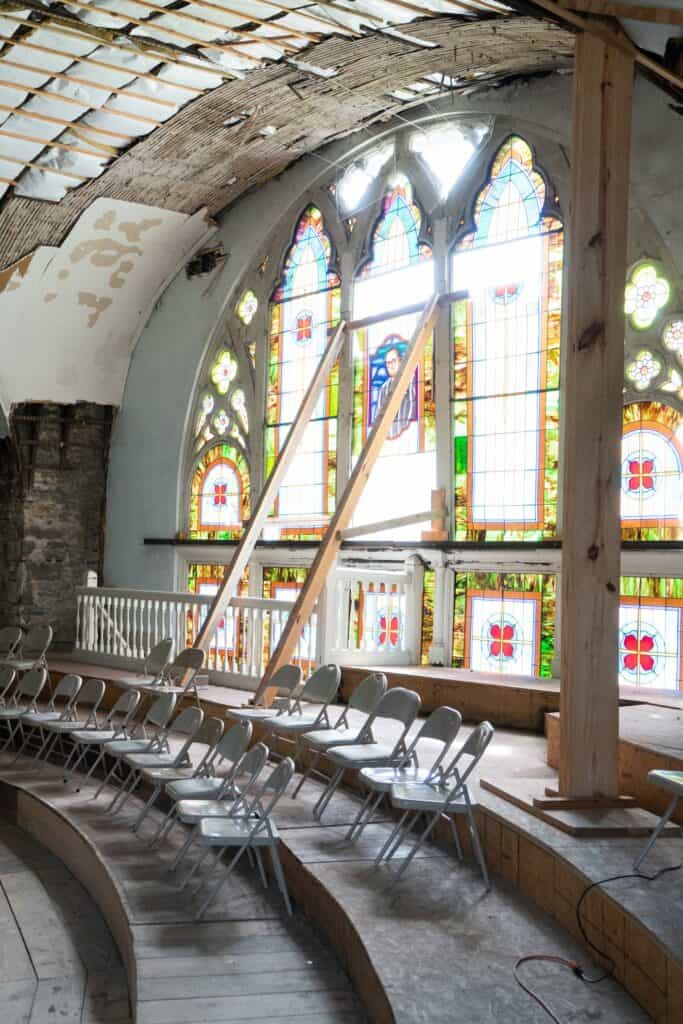

History and churchgoing have converged for almost 130 years at Clayborn Temple, and, after almost 18 years of disuse and neglect, efforts are now ongoing for its restoration. At the intersection of Hernando and Pontotoc, along the sidewalk just south of FedEx Forum, scaffolding soars skyward encasing the large limestone church. Through the nonprofit Historic Clayborn Temple, work is well underway to restore the building to its look in March 1968, when it served as the headquarters for the sanitation workers’ strike that brought Martin Luther King, Jr. to Memphis. Anasa Troutman, executive director of Historic Clayborn Temple, expects a fall or winter 2024 reopening as a cultural arts center and performance space for storytelling and community gathering.

The history begins in 1891 when Second Presbyterian Church paid $100,000 for building of the Romanesque Revival style church, with soaring timber trusses, a chancel section in the corner of the building, unique stained glass, and a large organ with 2,193 pipes. Dedicated on January 1, 1893, at the time it was the largest church south of the Ohio River. According to the 1870 census the surrounding neighborhood was equally racially mixed–this was a thriving early Memphis neighborhood with Beale Street just to the north, several other churches nearby, and neighbors coming to church by foot and horse.

Beginning in the 1940s, though, some of the congregation started to move east. The change in the neighborhood was exacerbated by the Memphis Housing Authority seizure of 16 White homes and 428 Black homes to build public housing known as William H. Foote Homes. According to Troutman, oral histories of some of the civil rights activists at the time tell of changing demographics of the congregation and hesitancy of White parishioners to continue to attend church with their Black neighbors. “Eventually as the neighborhood was changing and it was becoming more diverse and things were heating up around civil rights in the ‘50s, there was a lot of contention about the congregation not wanting to worship with Black folks and there was a lot of tension inside of the church congregation.” Eventually this tension led to the sale of the building to the African Methodist Episcopal (AME) Church in 1949 and it became Clayborn Temple, named after its pastor, Bishop J.M. Clayborn.

While we love the building we also want to think about how the building is going to serve the community and so we have already started our community programming. We not only want to tell the story of the sanitation workers but we also want to be able to continue their legacy of being able to do the work, creating space to have economic equity and dignity as human beings. We have a series of programming that’s designed specifically for conversations and action around the intersection of race and class.

Anasa Troutman

Because of its proximity to downtown and its investment in community and civil rights work, Clayborn was chosen as the headquarters for the sanitation workers’ strike of 1968. Former sanitation worker T.O. Jones had worked for years to galvanize the union around the need for improved safety standards and better wages. On February 1, 1968, two sanitation workers, Echol Cole and Robert Walker, taking refuge from a rainstorm, were killed in a malfunctioning garbage truck. Ten days later the sanitation workers asked the Sanitation Department for union recognition, improved conditions, and better pay, and when denied they decided to strike. With Clayborn Temple as base, the workers walked daily from the temple to City Hall to protest and then returned to Clayborn where people collected clothes, money, food, and other donations to support the strikers. Rev. Malcolm Blackburn and Cornelia Crenshaw printed the “I AM A MAN” slogan for marchers’ signs in Clayborn’s basement.

At the invitation of James Lawson, local Methodist preacher and member of the strike committee, Martin Luther King, Jr. came to Memphis to join the cause of the sanitation workers, bringing focus to his interracial movement for economic justice, saying in a speech on March 18, 1968, at the Mason Temple, “You are reminding not only Memphis, but you are reminding the nation that it is a crime for people to live in this rich nation and receive starvation wages.” King returned to Memphis on March 28 and led a march where violence broke out. Police followed marchers back to Clayborn, surrounded the building, and threw tear gas through the stained glass windows. Originally listed on the National Register in 1979 for its architectural significance, the civil rights era events brought Clayborn “National Treasure” recognition in 2017, and some funding for restoration from the National Park Service. I AM A MAN Plaza next door to Clayborn opened in 2019 and highlights the events of February to April 1968.

Following the 1970s, the AME Church congregation declined and couldn’t afford to keep the building open. Around 2000, they locked the doors and walked away. Clayborn stayed closed for about 15 years. In 2015, Clayborn was purchased by Neighborhood Preservation, Inc., which conducted a stabilization effort so the building could host events such as MLK50 in April 2018. Troutman came to Memphis as executive producer of “Union: The Musical,” which was performed at Clayborn as part of MLK50, and she continued work as part of a team making long term plans for the building. She became executive director of the nonprofit Historic Clayborn Temple, which bought the building in December 2019.

After the long period of disuse, the building was in poor shape, with one of the roof trusses broken and compromised walls and windows. After closing in 2019 for repair, the team at Historic Clayborn Temple navigated an extensive process to gain approval of restoration plans from the National Park Service, which required them to restore the building as close as possible to the time of national significance in early 1968. The restoration process is currently in phase 2, which includes the exterior envelope– a new roof, new truss infrastructure, many new stained-glass windows, and masonry–making the building sound structurally. Hands-on restoration began in October 2021. The exterior of the building has been cleaned and repaired, and the interior will be restored to its 1968 aesthetic, except for modular seating on the first floor and pews only in the balcony. Allworld Project Management of Memphis is managing the construction. With about five months to go on the exterior, they expect to begin interior work in fall 2023 as long as fundraising allows.

Troutman feels confident they can raise the needed funds. “We have over $2 million to raise. We have probably raised upwards of $6 million at this point to get through the purchase of the building and phase 2 of the exterior envelope. I’m really, really proud of what we’ve already been able to do from a fundraising standpoint but we have a long way to go.” Shelby County has contributed $1 million. Next steps include focusing on assistance from Memphis. The efforts and work completed have shown they will get the work done. “We believe in this project and we believe in this city and we want to be a meaningful contribution to the future of Memphis. We are hoping to be able to work with the partnerships that will make that possible.”

Two prominent features of the building have gotten special attention. The stained glass west window is about 95% original and is the only large scale stained glass remaining. The windows that were damaged or replaced will be redesigned by local artists telling the story of the strike. The large organ is a unique instrument installed in 1892 and the plan is to restore it to its full function. Much of the pipework was destroyed or is missing but the pipes that remain are restorable.

Troutman says she is working to tell Clayborn’s story. “It’s a really important building. It is a sacred space but it is also a part of American history. It is the reason why MLK came to Memphis when he was assassinated, and that is a story that must be told, and so I tell it as often as I can and hope that people feel compelled to support our work.” The effort has been, well, historic. “I never dreamed I would be a developer. I certainly didn’t dream I would be a historic preservationist or restorer. So it’s been really interesting as an individual, as an artist, as a producer, as a leader growing into this role being able to lead such a huge team. Being able to be in a role that I’m still learning about has been one of the most interesting, compelling, and challenging times of my life,” Troutman says.

The location of Clayborn also highlights the mission of creating a link with downtown and historically Black Memphis. “We’re right next door to FedEx Forum. We are in an excellent location, accessible to all people, welcoming to all people, and creating space for us to be able to have the conversations that are hard to have in those spaces and doing that in a historic building makes it that much more powerful,” Troutman notes. She explains that it is important for people to see themselves in the work and in the history of this building. “Because we know that it wasn’t just the Kings of the world that changed the world, it was the everyday people like Cornelia Crenshaw, T.O. Jones, and James Lawson who were everyday people who decided that they wanted to see the world a little bit differently, and so they came together to do that work. So we want to be a place where people are welcome, their vision is welcome, their stories are welcome, their vision they have for the future of themselves and their families is welcome.”

Restoring the neighborhood around Clayborn is also a priority. Troutman elaborates, “While we love the building we also want to think about how the building is going to serve the community and so we have already started our community programming. We not only want to tell the story of the sanitation workers but we also want to be able to continue their legacy of being able to do the work, creating space to have economic equity and dignity as human beings. We have a series of programming that’s designed specifically for conversations and action around the intersection of race and class.” This focus will include building an additional space behind Clayborn where there had been a gym that was burned and removed. “That building will be replaced by a second building that will be committed to community work, to having folks come and learn about restorative economics and figure out ways that they want to participate in healing the economy of their own communities starting with their own neighbors….It’s going to have a green roof and will house all kinds of wonderful things happening in that space for the community in the neighborhood.”

Troutman talked about the elegance of the Clayborn space, its intersection of history and social justice, and its potential for the city. “Something that’s so unique about this space is, as you know, Memphis is a very segregated city with lots of turmoil around race and class. We hope to be one of the places where people can come together and heal those divisions because we are both a part of the history of the Presbyterian Church, which is historically White, and also the AME Church, which is historically Black. Everyone in Memphis feels like they have ownership and claim to the history of the space, which is absolutely true.” It is true that Memphis eagerly awaits Clayborn’s renewal.